Education

Shortly after the Civil War began, African Americans, both free and enslaved, quickly took advantage of any chance to gain the education that had been denied to them under slavery. Despite widespread and often violent opposition from white Virginians, opportunity came from a variety of sources. In parts of Virginia under the control of the U.S. Army, local African Americans and Northern missionaries established schools for both children and adults. The Freedmen's Bureau created public schools for African Americans after the war, and Virginia's 1869 state constitution authorized the state's first public school system for all children. The teachers—northern and southern, white and black, evangelical and secular, and even some Confederate army veterans—came to the job with a variety of agendas concerning what should be taught, how it should be taught, the extent of freedpeople's capacity for learning, and, ultimately, how education should prepare the African American community for postwar America.

Many whites, southern and northern, doubted that the freedpeople could succeed. Former Confederate officer Giles Buckner Cooke (1838–1937), who later established a divinity school in Petersburg for African Americans, described former slaves as "ignorant, credulous, superstitious," but he hoped that his educational work would transform them into responsible citizens. Teachers reported the desire and the ability of freedpeople to learn quickly and to advance their education. Practical education was an important part of the curriculum, and textbooks for freedpeople promoted thrift, piety, forgiveness, hard work, and the value of education. Many white southerners, however, felt threatened by northern teachers who advocated social equality. Across the state teachers, students, and schools faced violence, including thrown rocks, gunfire, and arson.

Individuals began opening schools as soon as the presence of U.S. Army troops provided a measure of security. Numerous religious and private organizations sent people to coastal Virginia to teach in schools established for the freedpeople and to assist them in other ways. One such group was the American Union Commission, which was "constituted for the purpose of aiding and co-operating with the people of those portions of the United States which have been desolated and impoverished by the war, in the restoration of their civil and social condition, upon the basis of industry, education, freedom, and Christian morality."

In September 1861, Mary Smith Kelsey Peake (1823–1862), who had been born free in Norfolk, began teaching under an oak tree (later known as the Emancipation Oak) at Fort Monroe. Even while bedridden with the tuberculosis that killed her, Peake taught hundreds of the many African American men, women, and children who had escaped from slavery to the safety of the army's camp there.

U.S. Army Major General Benjamin Butler continued Mary Peake's work by using government funds to construct a school at Fort Monroe. The site of the Butler School later became part of Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (later Hampton University), when it was established by former U.S. Army officer and Freedmen's Bureau official Samuel Chapman Armstrong in 1868. Intended to train black teachers to educate other African Americans, Hampton was coeducational and within a decade its male and female graduates were teaching thousands of African American children across the state and the South.

The Freedmen's Bureau provided the infrastructure to create, maintain, and administer schools across Virginia and the South. In 1865, it created the first statewide school system in Virginia. Many of the schools relied on funding, supplies, and textbooks provided by such northern missionary and aid societies as the American Missionary Association and the New England Freedmen's Aid Society. During and after the Civil War, African Americans had met in schools held in any space possible, including churches, private houses, former military buildings, and even outdoors. The Freedmen's Bureau provided funds to construct new buildings, and some of the contracts went to African Americans, such as George Lewis Seaton, a contractor who had been born free and who served in the House of Delegates in 1869-1871.

The Constitutional Convention of 1867–1868, which included two dozen African American delegates, authorized a public school system for all of the state's children. When William H. Ruffner, Virginia's first superintendent of public schools, wrote the act to create the public school system in 1870, legislators insisted that the schools be racially segregated. That provision led some of the African American delegates and senators, including Seaton, to vote against the bill, which they undoubtedly favored. Most white Virginians feared that interracial schools would lead to "race mixing" and overturn what they considered to be the proper order of society.

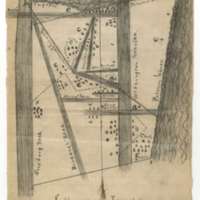

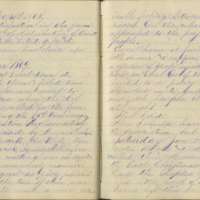

As local officials complied with the new state law, they set about drawing school districts segregated by race. This could be a challenge, however. This hand-drawn map of Jefferson Township (in what was then Alexandria County, part of present-day urban Arlington), shows white and African American families living closely together. To create two districts segregated by race, the mapmaker drew what looks like a badly gerrymandered voting district with each dwelling designated as W ("white") or C ("colored").

Some teachers who had taught in the Freedmen's Bureau schools or in schools that northern churches and reform organizations sponsored remained in Virginia and taught in the new public schools. Pennsylvania native Jacob Eschbach Yoder (1838–1905) taught in a Lynchburg school that the Pennsylvania Freedmen's Relief Association sponsored, later joined the Freedmen's Bureau, and remained to become principal of the city's racially segregated public schools. Despite his idealistic intentions and notable successes, he confided to his diary his deep ambivalence about his job, the abilities of his colleagues, and the prospects for African American education.

The new public school system immediately became extremely popular among all Virginians. Before the Civil War, African Americans had been forbidden an education and many white children had lacked access to schools. The expense of paying the interest on Virginia's prewar public debt threatened the existence of the public schools, however, and before the end of the 1870s many black and white Virginians united in a biracial political coalition known as the Readjuster Party. The Readjusters were able to refinance (or readjust) payment of the debt and increase appropriations for public education early in the 1880s. Public schools remained inadequately funded in most parts of Virginia for many decades. Schools for African Americans were often inferior in size and quality to schools for white children. Not until after the Supreme Court's 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education did Virginia desegregate its public schools.