Violence

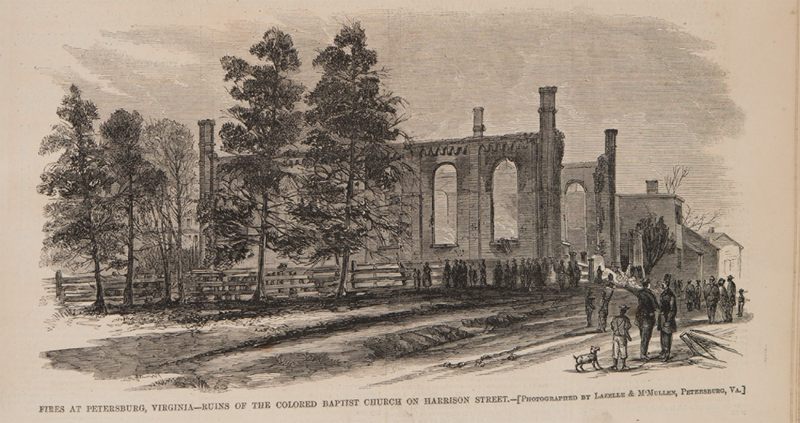

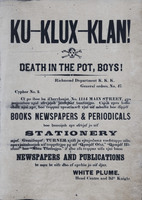

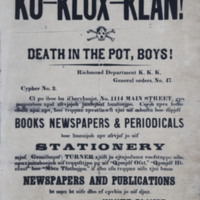

Black expectations of freedom and personal, political, and economic autonomy after the war ran headlong into white intransigence. In wiping away slavery, emancipation erased the very foundation of Virginia culture. Many white people, embittered by the war and the destruction of the antebellum model of race relations, attempted to enforce labor contracts, social mores, and claims to political supremacy, sometimes violently. Personal confrontations between workers and landholders ended in beatings or murders. Some white Virginia judges ordered that blacks be punished at the whipping post as in slavery times. White people sometimes attacked and burned African American churches and schools that represented a threat to the old racial order and provided rallying points for black political action. In the spring of 1868 a few white Virginians organized local chapters of the nascent Ku Klux Klan to intimidate African Americans and its leaders warned members to "Beware of Africanns" before disbanding within a few months.

Freedmen's Bureau agents often intervened on behalf of freedmen if local courts did not provide justice. Agents reported seventy-two "Outrages in Virginia" against freedpeople from April through July 1866 and ninety in the year 1868. Despite Freedmen's Bureau courts and the presence of federal military commanders from 1866 to 1868, many violent acts went unpunished. Mannie Ballard, an African American man living in Isle of Wight County, went to court in 1866 after he and his child were shot at and his wife beaten, but he feared naming the white men who had attacked them "for fear of assassination," and the Freedmen's Bureau agent could not take action on his behalf. An agent in Franklin County reported that same year that local justices of the peace refused to recognize in court white men who had been accused of any crime against an African American.

Some white government officials in Virginia attempted to deprive African Americans of firearms. In November 1865, the Norfolk County Court petitioned the officer of the Freedmen's Bureau in Norfolk to take such action after local white residents complained about African Americans "in the habit of bearing arms," whom they described as "prowling about during the hours of the night, plundering property and engaging in other unlawful acts prejudicial to the good order and interests of Society."

Tensions between blacks and whites boiled over in Norfolk on April 16, 1866, when a parade of African Americans celebrated Congress's passage of a national Civil Rights Act. The demonstrators carried banners for fraternal and political societies. Some white people threw rocks and bricks at the parade, and a fight between marchers and a city police officer began after the accidental discharge of a gun. Violence continued through the night as armed bands of whites attacked blacks, killing two and injuring several others. United States troops declared martial law to control the mobs.

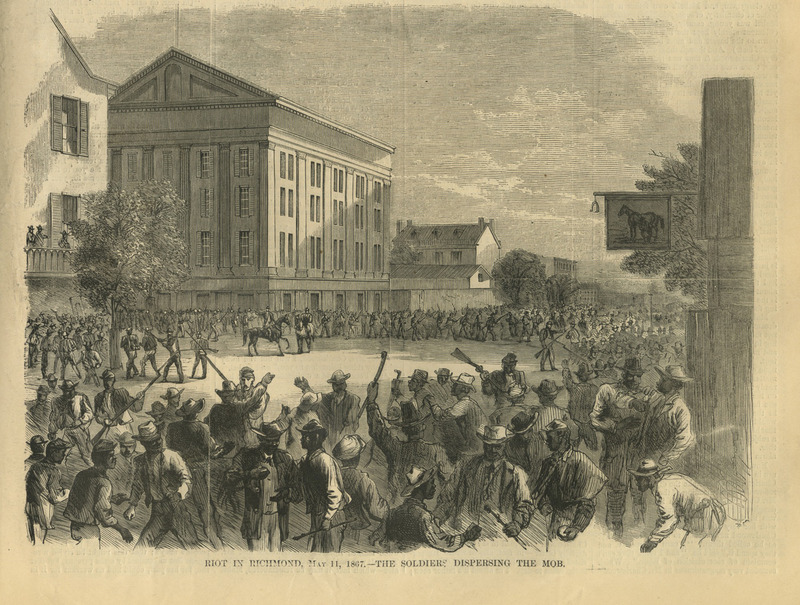

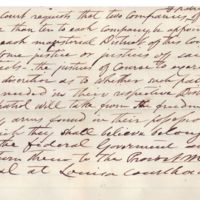

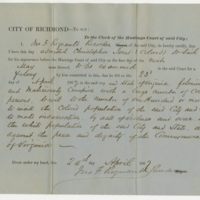

In the spring of 1867, Richmond was a city filled with tension. Former Confederate president Jefferson Davis was expected to stand trial for treason in the city's federal court. African Americans were holding political meetings and were protesting their treatment by whites. In April, African Americans organized protests against the privately operated company that refused to allow them to ride the city's streetcars. Christopher Jones had tried to board a streetcar and was arrested for disturbing the peace after a large crowd assembled to support his insistence that, having bought a ticket, he was entitled to ride the streetcar. African Americans in the crowd reportedly shouted, "Let us have our rights," "We will teach these d—d rebels how to treat us," "We have petitioned General Schofield (the army commander in Richmond) about it, and he won't do anything," and "We must take the matter in our own hands." Jones was indicted for conspiring to "incite the Colored population of the said City and State to make insurrection by acts of violence and war against the white population," but the court did not prosecute him.

Elections were also flashpoints of violence in Virginia and across the South. White people who strongly resented African American elevation from slave to citizen and who feared their exercise of the franchise attacked polling places to prevent black men from voting and also to harass and beat Republican candidates. In February 1870, open political conflict broke out in Richmond. The General Assembly appointed a new Richmond city council that in turn appointed Henry K. Ellyson mayor until a new election could be held in May. The incumbent mayor, George Chahoon, refused to resign. For several weeks Richmond had two city governments struggling for control of the city. During a standoff between white Conservatives and Radical Republicans a general melee broke out. Crowds showered the fleeing police with bricks and stones and the police fired into the crowd, killing a black spectator named Daniel Moore.

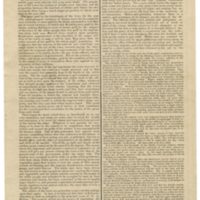

Before the 1883 general election, white residents of Danville appealed to people elsewhere in Virginia to vote for Democrats in order to defeat the biracial coalition known as the Readjuster Party, which had won control of the General Assembly and all the statewide offices two years earlier. Readjusters were also prominent in Danville's city government, with the result that African Americans for the first time held public office in the city, including as police officers. A circular letter published with the Staunton Vindicator voiced the racial attitudes common among white Virginians at the time and fueled resentment at what many of them regarded, inaccurately and unfairly, as African American domination of Virginia's society and government. A few days before the November 1883 election, a street brawl took place in Danville between black and white residents. Skillful Democratic political leaders used the violence to support their claim that the Readjusters and Republicans posed a serious threat to white supremacy. The so-called Danville Riot of 1883 and the general election a few days later were important events in the return to political dominance of white political leaders opposed to African American suffrage and officeholding.

Violent conflicts between individuals of both races as well as organized violence characterized Virginia and other southern states throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century. The state's courts continued to sentence African Americans convicted of some crimes to humiliating and painful public whippings until 1882, when the General Assembly outlawed "punishment by stripes." Forty-nine well-documented lynchings occurred in Virginia between 1880 and 1900, and thirty-seven more between 1900 and 1930. During the 1920s, some white Virginians reestablished local chapters of the Ku Klux Klan, which had previously existed in the state for only a few months in 1868.