The End of Slavery

The end of slavery occurred incrementally in Virginia. Throughout the history of slavery in the state, enslaved people used different strategies to attain freedom. Some ended their own enslavement by running away. Some conspired together to end their enslavement through violence. Others sued for their freedom on the grounds that they descended from a female American Indian, some of whom had been illegally enslaved during the eighteenth century.

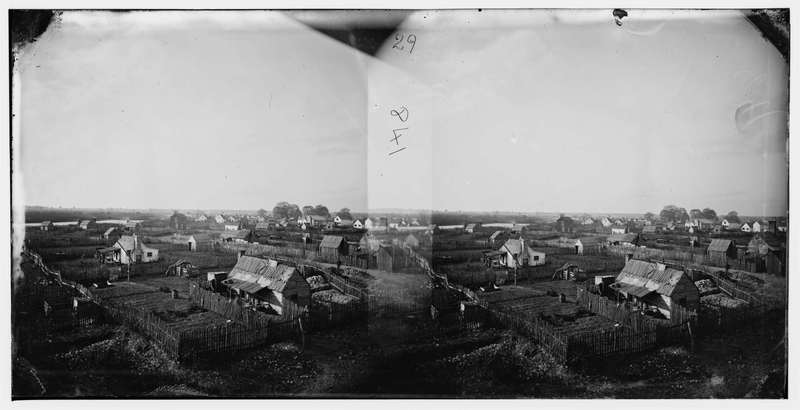

With the start of the Civil War, enslaved people sought refuge with United States troops. In May 1861, at Fort Monroe, General Benjamin F. Butler declared such runaways as "contraband of war" (in effect, confiscated property) to deprive the Confederate States of America of their labor. During the war, as the number of "contrabands" increased, the federal government moved toward granting them freedom. Refugees formed large communities in Hampton and also on the grounds of the Lee family mansion, Arlington, in northern Virginia.

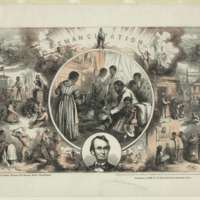

The Emancipation Proclamation, effective January 1, 1863, freed enslaved people only in areas "in rebellion" against the United States. As Union troops captured parts of Virginia, commanders used the authority of the Emancipation Proclamation to declare enslaved people free. On April 7, 1864, a constitutional convention for the Restored Government of Virginia, then meeting in Alexandria, abolished slavery in the part of the state that remained a loyal member of the United States. The General Assembly of the Restored Government ratified the proposed Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which abolished slavery, on February 9, 1865. When the amendment was ratified by the required two-thirds of state legislatures on December 6, 1865, slavery ceased to exist everywhere in the United States.