Families

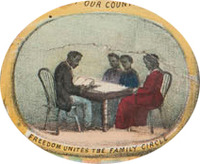

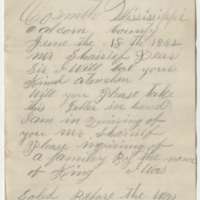

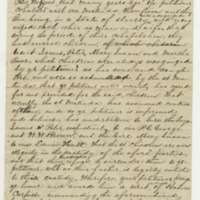

The interstate slave trade had brutally disrupted African American families. Emancipation offered couples the opportunity to marry legally and live with their children as a family. Many formerly enslaved people searched for mothers, fathers, spouses, children, or siblings who had been sold, seeking to reconnect, even if they could not reunite. Emancipated African Americans faced obstacles unimaginable to white Virginians. As they searched for children and spouses, disputes arose over who controlled the labor of children from earlier relationships. African Americans advertised in newspapers, worked through the Freedmen's Bureau, and even wrote letters to governors and county sheriffs trying to locate family members.

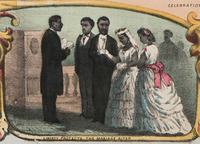

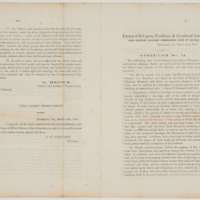

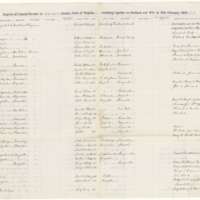

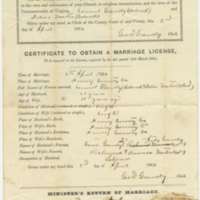

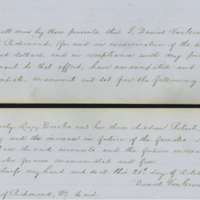

Before 1866, Virginia law did not recognize slave marriages. In 1865 Oliver Otis Howard, commissioner of the Freedmen's Bureau, directed county clerks to register such cohabiting couples. On February 27, 1866, the General Assembly enacted legislation to legalize the "Marriages of Colored Persons now cohabiting as Husband and Wife." The information recorded in the registers is invaluable to genealogists and historians. The documents reveal that despite Virginia's refusal to recognize slave marriages as legal, many slaves considered themselves married and lived as husband and wife, raising families as best as they could given the cruelty of slavery. Bureau officers also compiled separate registers for the legitimization of children whose parents were no longer living together, and the law for the first time authorized county clerks to issue marriage licenses to African American couples. The law also prohibited interracial marriage.

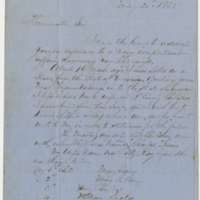

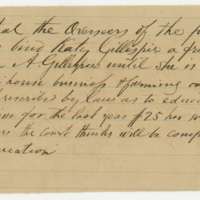

Legalization of marriages and legitimation of children did not resolve all issues that African American families faced. Because some people had been sold away from their families or had escaped from slavery and had subsequently remarried, legal complications often arose concerning inheritances or child custody. In 1867, for instance, Peter Wiggins petitioned the Westmoreland County Court for a writ of habeas corpus to gain custody of the two sons and two daughters he and Malinda Thompson had before the Civil War; but because Wiggins had been married to a woman named Ann when the 1866 cohabitation act was passed, the judge ruled that the children of Peter Wiggins and Malinda Thompson were illigitimate and refused to award custody of them to Wiggins.

During slavery times, orphaned slave children were the responsibility of their owners. In 1866 the General Assembly authorized local overseers of the poor to "bind out," or apprentice, orphaned or homeless African American children to responsible adults to raise, educate, and provide training in some useful occupation. The Virginia Constitution of 1864 specified that all orphaned Virginia children, including freedpeople, be treated in the same manner as overseers had previously treated white orphans.

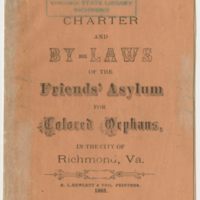

Lucy Goode Brooks (1818–1900) had a special concern for the plight of parentless children. She and her husband, Albert Royal Brooks, had lived with their children in slavery in Richmond. In 1858, he bought and freed her and their three youngest children. She persuaded local men to buy their other children to keep the family together, but the man who purchased their eldest daughter broke his promise and sold the girl to a buyer in Tennessee. Having lost a daughter to the slave trade, Brooks wanted to help children in Richmond who looked for family members after emancipation. In 1871 she convinced members of her Ladies Sewing Circle for Charitable Work as well as several black churches and the local Richmond Society of Friends (Quakers) to open the Friends' Asylum for Colored Orphans, which still exists as the Friends Association for Children.