African Americans Vote

African Americans in several states, including Virginia, voted for the first time in the autumn of 1867. Radical Republicans in Congress had become frustrated during the winter of 1865–1866 with the opposition that many white southerners exhibited to extending full rights of citizenship to African Americans. In June 1866 Congress submitted the Fourteenth Amendment to the states for ratification. It made African Americans citizens and prohibited states from passing or enforcing any laws "which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."

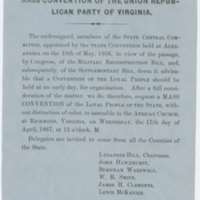

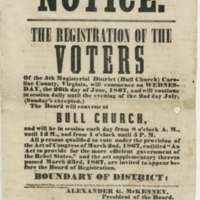

In the spring of 1867, Congress passed the Act to Provide for the More Efficient Government of the Rebel States, often called the First Reconstruction Act. It required the former Confederate states to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment before their representatives and senators could be seated in Congress. It also required the states to hold conventions, in which African Americans were eligible to serve, and to write new state constitutions. In Virginia, African Americans, former Unionists, and men who had settled in Virginia during and after the war organized to prepare for the election. Officers of the U.S. Army oversaw the registration of voters.

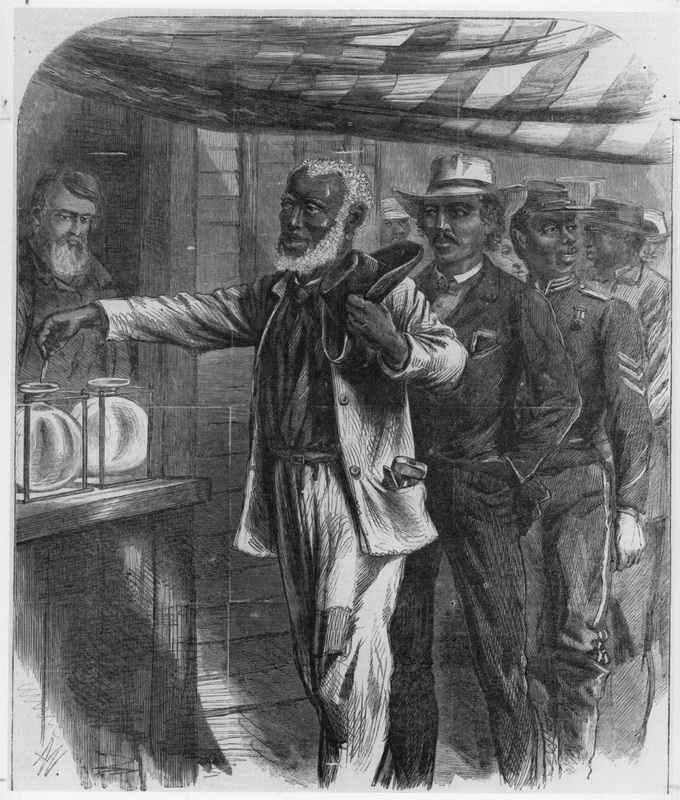

On October 22, 1867, African American men voted in Virginia for the first time. The army officers who conducted the election recorded the votes of white and black men on separate lists and in some or all of the counties and cities required voters to place their ballots in separate ballot boxes.

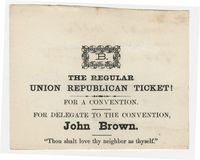

Many white Virginians who opposed Republican Reconstruction policies refused to take part in the 1867 election. As a result, Republican reformers (many of whom were identified as radicals), won a majority of seats in the convention. Twenty-four African Americans won election to the convention. Some had been free before the war, but many had become free as a consequence of the war. Among them was John Brown (ca. 1830–ca. 1900), who had lived in slavery in Southampton County and emerged as a leader of the freedpeople after the war. With his campaign slogan, "Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself," printed on the ballots he distributed to men who voted for him, he defeated two white candidates to win election to the convention.

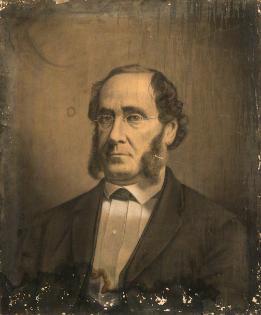

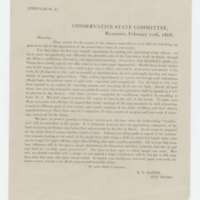

Soon after the constitutional convention began its work, a large gathering of white men met in Richmond on December 11–12, 1867, to form a new political party in opposition to the radicals in Congress and in the convention. They created a new Conservative Party that united members of the two prewar political parties, Whigs and Democrats. Most of them opposed African American suffrage and had difficulty accepting the new reality created by the abolition of slavery—changes that the radical reformers in Congress threatened to make permanent. The Conservative Party's state chair, Raleigh Travers Daniel, issued a series of instructions during the winter of 1867–1868 to recruit members. Circular No. 4 appealed to white men who feared "negro suffrage, negro office-holding, and negro equality generally."

The Conservative Party did not repeat the mistake that opponents of the constitutional convention committed in 1867 when they refused to take part in the election of delegates. They mobilized a substantial majority of Virginia's white voters, and Conservative Party candidates won a majority of seats in the General Assembly election in July 1869.