Abolitionism

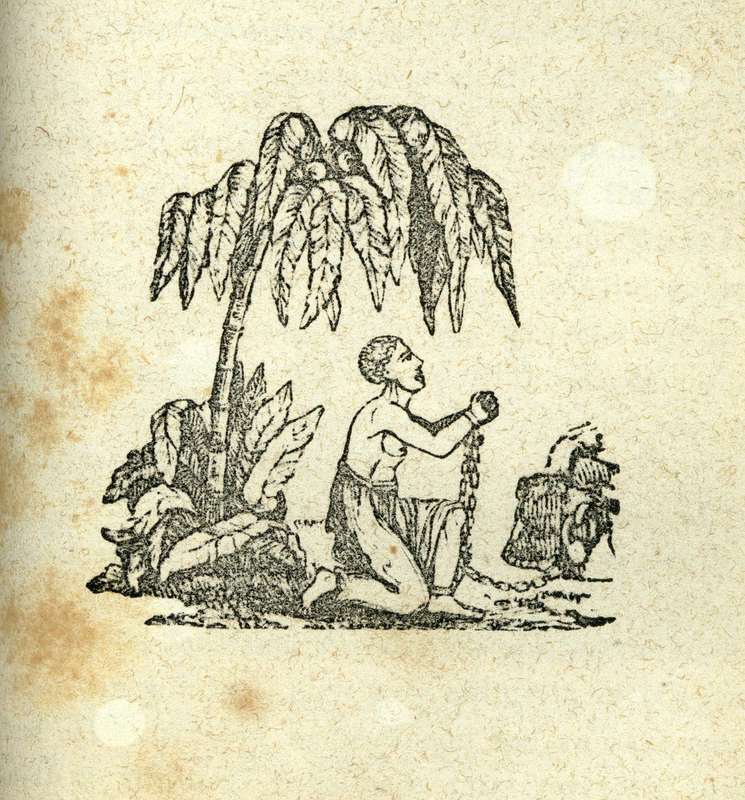

Founded in England in 1787, the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade campaigned in Parliament, wrote pamphlets and books, and published images to raise awareness of the horrible conditions of the Middle Passage. In 1807 Parliament passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, thus ending Great Britain’s participation in the international slave trade. In 1808 the United States also ended its participation in the Atlantic slave trade.

Opposition to slavery in the United States developed unevenly. At various times between the American Revolution and the 1807 federal law banning the importation of African slaves, some states, including southern ones, discussed gradual emancipation and/or manumission of enslaved people. States such as Vermont and Massachusetts banned slavery outright, while others, such as Rhode Island and New York, adopted a gradualist approach. Beginning in the 1810s, Quaker anti-slavery activists in the South and some southern slaveholders were particularly active in the colonization movement that relocated free and formerly enslaved African Americans to the state of Liberia in West Africa. The Virginia legislature openly discussed abolition in 1829 and 1831. By 1840, virtually all African Americans living in the North were free.

Those who called for an immediate end to slavery, called abolitionists, were centered in New England, especially in Massachusetts, and considered by many to be radical and dangerous in their political views. In 1831 William Lloyd Garrison began publishing the Liberator, among the first of what was to become an onslaught of anti-slavery publications: newspapers, pamphlets, books, and broadsides. Abolitionists also tried to build support for their movement through meetings and fund-raising bazaars with speakers such as Frederick Douglass and Wendell Phillips. At the beginning of the Civil War, abolitionism was still a small political movement and a greater number of Northerners favored a gradual approach to ending slavery. In response to abolitionist agitation, southern slaveholders developed a "positive good" argument in support of the "peculiar institution."