The Interstate Slave Trade

“Richmond is the great Slave Market for the South”

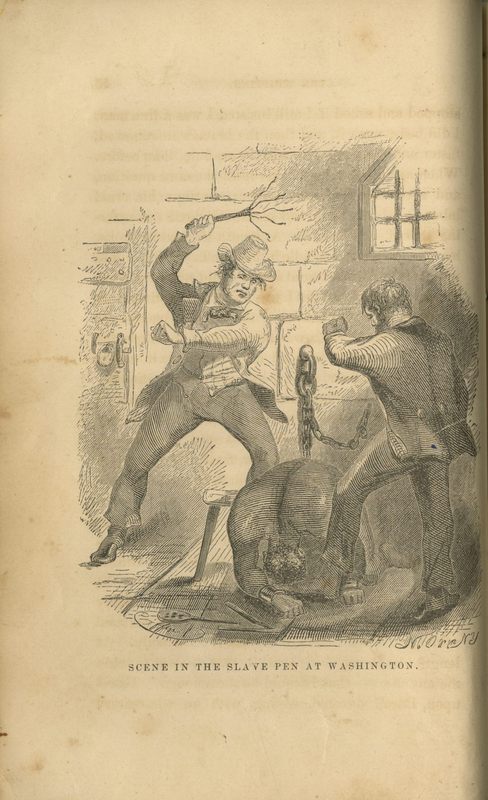

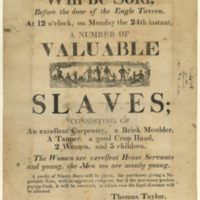

The Upper South cities of Baltimore, Washington, D.C., Alexandria, Norfolk, and Richmond became slave-collecting and resale centers. A large network of traders worked in the surrounding counties, purchased people, and sold them in the urban markets. Before being sold to traders who supplied labor for the cotton and sugar plantations in the Deep South, the enslaved were kept in special jails, commonly a small compound of buildings that consisted of a dwelling house where the trader lived, a kitchen, and a building with bars on the windows, where those awaiting sale could be locked up. Most compounds also had an outdoor space where the people awaiting sale were exercised in order to prepare them for sale. The men and women sent to these jails remained there for a matter of days or sometimes for weeks. As one owner directed the trader R. H. Dickinson, "Offer [Richard] for sale at public auction at your auction room if they are selling tolerably well…" but if they are not, "confine him in gaol" until the prices rise.

Many people were held in jail for weeks or months, some until their physical condition improved and others until prices rose to maximize the traders' profit. Former slaves reported that while there they were fed, given medical treatment, and made to look young and healthy. John Brown, who was traded from Virginia to Georgia to New Orleans, recalled "There was a general washing, and combing, and shaving, pulling out grey hairs, and dying the hair of those who were too grey to be plucked without making them bald." The enslaved received new clothes and shoes. They were dressed for sale.

Slave traders used the threat and practice of physical punishment to control those they were about to sell. Buyers examined the people they planned to buy, looking for evidence of scarring from earlier beatings. Slave traders themselves developed a range of descriptions to measure the evidence: "not whipped," "a little whipped," and "considerably scarred by the whip." Evidence of multiple incidents suggested that the person ran away frequently. Old scars meant that a person’s behavior had been modified.

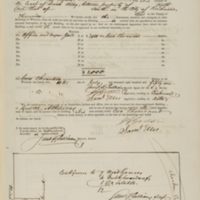

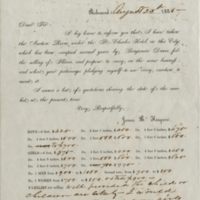

The slave trade is extensively documented through the daily scraps of paper that detailed business transactions. Ledgers, receipts, insurance policies, and price lists coldly record the business of selling people. Traders' letters to one another obsessively discussed prices, as did those from slave owners who were considering selling. It was such a regular part of the business that some traders even had forms printed so that they could fill in the latest "state of our Negro market." As seen on these circulars, the people being sold were classified: "Extra," Second rate," or "Ordinary" were terms applied to men and women. Children were usually priced according to height.